|

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Calcutta: Society and Change: 1690 - 1990; "Introduction"; Rupa & Co publishers,1991. |

| CALCUTTA

is on the east (which happens to be the left ) bank of the Hooghly, the

most easterly of the distributaries of the Ganga in its large delta spread

over approximately 70 sq. km. Job Charnock chose this site on August 24,

1690, and it has since been criticized as an erroneous selection, as all

other European settlements - Hugli, Chinsurah, Chandernagore and Serampore

- were all on the western bank. Tamluk, the port founded several centuries

before Christ, and Nabadip - in the 11th Century A.D. - were also on the

western bank. Rudyard Kipling, the mildest of the critics, wrote 200 years

later that it was "chance directed", but that was probably because Calcutta

had grown into a city bigger than Bombay where the poet was born. Even

imperialists suffer from parochialism.

Events have proved that Charnock was not wrong - at least had not been so for 257 years till partition robbed the city he had founded of a large part of its hinterland, by bringing the border as close as 77 km. The border, like most borders, was as much economic as political. Nobody in Charnock's time or even ten years before the happening could have foreseen partition. Charnock was led to Sutanati and adjoining Kalikata by the weavers (Basaks) and traders (Setts) - who had settled at the former place as early as the fifteenth century (i.e. before the Portugese had sailed up the Hooghly in 1510; and possibly before Vasco da Gama had discovered the 'Cape route' between Europe and India in 1497); he was definitely not led by chance!The Setts and Basaks had come to Sutanati and Kalikata because it was nearer the the sea, and the Betor canal connecting the Hooghly with Satgaon was silting up. According to Sir Evan Cotton, Charnock came to Calcutta because "The Bengali families which have been so closely associated with British rule in India - the Setts, the Bysaks, the Mallicks (ancestor Rajaram of Trevene [Triveni]) - advised Charnock to transfer the Company's Factory from Hooghly to Sutanati". The Hooghly had been an important waterway for more than 3000 years. Tamluk (a shortened form for Tamralipti) - lower down the river - gets its name from the copper which was mined, as it is even now, at Ghatsila, not far from the port. Copper had been eclipsed by iron around 100 B.C.. So the name must have originated during the Copper Age, when Tamralipti exported the ore and metal to peninsular India, since the alternative was the less accessible Rajasthan area. The longer, original name of the port was in use till the third century B.C., when Ashoka's daughter and son sailed form it for Sri Lanka. Copper was replaced by other exports - mainly cotton goods - to South-East Asia. When the weavers and traders settled at Sutanati, they were most likely viewing prospects in the regions now known as Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. Since the East India Company, whose interests Job Charnock represented, had to economize on the bullion they spent on their purchases, export of goods to other Asian countries was as important a consideration as export to European countries. Sutanati was valuable in that context. Let us turn to an even earlier period - to the 18 centuries between the Ashoka siblings' voyage to Sri Lanka and the first entry of Portugese ships into the Hooghly estuary. Greeks knew of the delta (perhaps second or third hand) and called it Gangaridae, placing it further east of Parasii, their term for Magadha. Shards of Roman poetry and the clay cast of Augustan medallion have been found on the banks of the Hooghly, thereby pointing to Roman trade extending as far east in the early centuries of the Christian era. This trade, as well as Vasco Da Gama's crossing of the Arabian Sea from Malindi in East Africa to the Kerala coast, was helped by knowledge of the monsoons - winds blowing in a particular direction throughout a season. The same knowledge was used by Ashoka's children for their voyage to Sri Lanka. The Bay of Bengal is so shaped and situated, that the north-east monsoon wafts ships from the Hooghly outwards towards Sri Lanka and Java, and the south-west monsoon facilitated homeward voyages before the season of rains and storms sets in. The people of Bengal were mariners till the Sena Dynasty lowered the status of traders in the caste hierarchy, and sea trade was declared polluting. These acts might have been prompted by a desire to deny the Buddhist monasteries their principal source of income: donations from trades. These degradations and proscriptions were instrumental in ensuring the decline of Buddhism in Bengal. The needs of trade, however, could not be stamped out. On the west coast, where Islam had reached four centuries earlier than in Bengal, conversions to that religion ensured the continuance of the maritime tradition. Ibrahim, who piloted Vasco da Gama from East Africa to India, was a Gujarati Muslim. The Chinese and the Arabs took over the overseas trade, and both ranged over the waters from China to Africa. They crossed the equator but did not round the southern tip of Africa, for there seemed to be no produce worth picking up in Zululand. Some Indians, mainly Gujaratis and Sindhis, also participated in the trade. Bengalis had to rest content with the adventurers of Chand Saudagar and a few others. Trade with Europe, however, was still lucrative, although transactions had to be conducted through intermediaries - Arabs, Shirazis, Turks and Venetians. Upto Jeddah in the Red Sea, the trade route coincided with the pilgrim route of the Moslem Haj. Arabs were the principal carriers of both pilgrims and goods. The goods were handed over to Venetians to sell to the rest of Europe. The direction of and route of the trade was the same as with Rome in earlier times. Husain Alauddin Shah was ruling Bengal when the Portugese first entered the Hooghly estuary in 1518. However, by the time their first trading settlement was established in 1537, Sher Shah was the ruler of Bengal as well as the rest of North India. The Portugese located their settlement near Bandel, which is a popular mispronunciation of 'Bandar' - the Arabic word for harbour. Thus, it can be inferred that a port existed had existed at Bandel, about 42 km. upstream from Calcutta during the Arab supremacy over the seas around India. By 1580, the Moghuls had extended their authority over Bengal. It will be useful to recall two facts. First, the Portugese wielded some influence at Akbar's court, though from Goa and not form their settlement on the Hooghly. Second, Humayun had come in contact with Armenian traders during his refuge in Persia, some of whom followed him back to India. Armenians spoke Persian - the language of the Moghul court - and were Christians, though not of the same denomination as the Portugese. They were eminently suited to be middlemen. For 192 years the Portugese enjoyed a near monopoly of Bengal's trade with Europe, and their settlement at Hugli (named after the river but spelt differently to distinguish the town from the river) grew. It had the advantage of geographical location, only two kilometers away from Bandel and not too far from the earlier port, Satgaon, the temple town of Navadwip, and the administrative center of Panduah. In turn, Hugli attracted other settlements. The treasury had remained at Satgaon, the Customs House was located here too, and the Dutch built their settlement at Chinsurah, two kilometers south. The Moghuls did not compel anyone to turn Muslim and were tolerant of the Portugese, who, however, did not reciprocate. Portugese slave traders boasted in 1630 that they had made more Christians in one year than all the missionaries in ten. In 1629, Sha Jahan - annoyed with these forcible conversions - laid siege of the Portugese settlement at Hugli and in 1632, forbade their entry or residence throughout his territories. The church built at Bandel in 1599 was destroyed during the siege. Aurangzeb allowed it to be rebuilt in 1660. Till late in the 18th century, Roman Catholics around Bandel and Hugli boasted to an Italian visitor that they did not permit heretics ( by which they meant Protestants) to live among them. It is possible that they (the Roman Catholics) were equally intolerant of other Catholics, for the oldest Armenian Church on the banks of the Hooghly was built in 1707 in the Dutch settlement of Chinsurah, and not in Portugese Hugli or Bandel. Till the early 18th century, Chinsurah was well inhabited by Armenians. The Dutch were the first to challenge Portugese hold on Asian trade, but their original efforts were directed towards wresting the Indonesian islands from the Portugese. After having accomplished that, they established their settlement at Chinsurah in 1622 and other stations on the way to Chinsurah at Baluster, Falta and Baranagore. The Hooghly being subject to tides, intermediate halts were required when recession set in. Betor, near Sibpur opposite Calcutta, had been used as an anchorage by the Portugese; Falta and Baranagore by the Dutch. The English used Kulpi for that purpose till 1789, when they began developing Diamond Harbour. The Danes, who settled in Serampore and Gondalpara (now part of Chandernagore) around 1670, had a place for the purpose of lighting the burden of ships at a place below the confluence of the Rupnarain with the Hooghly. Chandernagore was founded by the French in 1688, and had a country house at Garati for its Governor. Chandernagore retained its identity longest, till 1947, when it merged into independent India. The Dutch settlements of Baranagore and Chinsurah were exchanged for British enclaves in Sumatra around 1824, while Serampore was purchased from the Danes by the British around 1845. Gondalpara was abandoned in 1714 and later incorporated into Chandernagore. How it is that the Portugese presence at Hugli inhibited all European nations other than the Dutch from establishing their settlements is not clear. However, the English, the Danes and the French came to the river after the Moghuls had driven out the Portugese in 1632. Sir Thomas Roe's embassy to the court of Jahangir in 1611 had cleared the way for the British to establish their trading settlements. However, they appeared in Golghat in the heart of Hugli town only in 1650, and had to leave in 1686, having incurred the displeasure of the Governor, Shaista Khan. The factory was re-occupied after Calcutta had been founded, but was in ruins through unuse. Throughout the 18th century, the English and the French were rivals in Europe, America and India, and often at war. English rivalry with the Dutch was less prolonged and less intense. During the 1757 troubles between the English and Siraj-ud-dowla, those evicted from Calcutta and Cossimbazar took refuge with the French and the Dutch. The settlements were not free to remain peaceful to each other once hostilities broke out in Europe. Within months of having received with gratitude French hospitality and succor, the English shelled and occupied Chandernagore from 1793 to 1813. The prolonged occupation robbed the French settlement of all its elegance, but even in its small town shabbiness it had "Liberte", "Egalite" and "Fraternite" inscribed on the gates which faced British India on the Grand Trunk Road running through the enclave. The Dutch had a less bitter and shorter experience of British ingratitude in 1759 fighting them on the Hooghly. Both the French and Dutch settlements were upstream of Calcutta, below which - between Thana (Sibpur) and Metiabruz - the half-mile width of the river was under the surveillance of guns mounted on watch towers with a chain drawn across. To storm through that stretch was possible only by a strong naval force which neither the French nor the Dutch could bring. Calcutta was suitably located for interception. To guard the settlements on the west bank, the British later built a large cantonment at Barrackpore, and a smaller one at Berhampore. Pilotage had been found necessary on the Hooghly since 1695. The number of pilot vessels depended on the traffic and a French visitor in 1789 noted that the English had twelve pilot brigs at the place which later came to be known as Sandheads. He was told that previously the French and the Dutch had a pilot vessel each. The fortunes of these two nations had by then declined beyond redemption. (end of chapter) |

|

Other references and links to historical information about Calcutta:

1. Calcutta: City of Palaces - A survey of the city in the days of the East India Company (1690 - 1858), by J P Losty (The British Library, Arnold Publishers).

2. Encyclopedia Brittanica, pp. 412-416 |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top |

| 2. Picture Gallery: Calcutta in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Source: 'Calcutta: City of Palaces' by J P Losty (British Libraries, Arnold Publishers); compiled by S. Mukherjee | |

| Click picture to enlarge | Description of Picture |

|

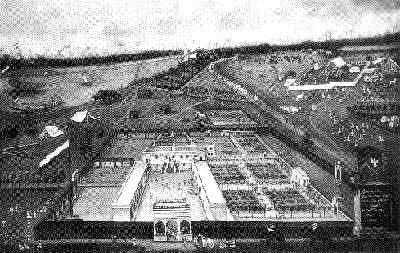

1.

The Dutch factory at Hooghly, Chinsurah, 1665

Oil on canvas, 203 x 316 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, A 4282 |

|

|

2. George Lambert (attributed), Fort William from the land side, with St Anne's Church c.1730. Oil on canvas; 81.5 x 130 cm.; Mafarge Assets Corp. |

|

|

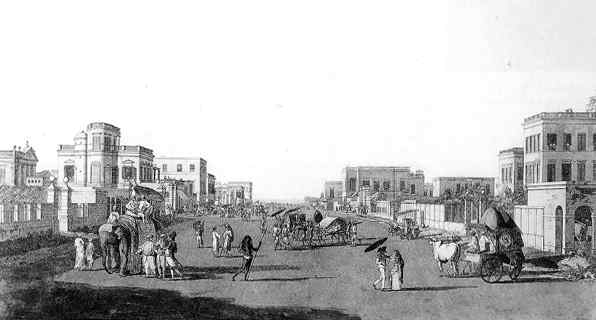

3. Thomas Daniel, Views of Calcutta #3; East side of Tank Square and the Old Mission Church, Calcutta 1786. Colored etching with aquatint; 40.5 x 53 cm. |

|

4. Thomas Daniel, Views of Calcutta #5; The new Court House, Calcutta 1787. Colored etching with aquatint; 40.5 x 53 cm. |

|

5. Thomas Daniel, Views of Calcutta #7; Houses on the Chowringhee Road, looking north, Calcutta, 1787. Colored etching with aquatint; 40.5 x 53 cm. |

|

6. Thomas Daniel, Views of Calcutta #9; Old Court House Street from the north, Calcutta, 1788. Colored etching with aquatint; 40.5 x 53 cm. |

|

|

7. Thomas Daniel, Views of Calcutta #10; Esplanade Row West with the Council House, Calcutta, 1788. Colored etching with aquatint; 40.5 x 53 cm. |

|

|

8. Anonymous view, Calcutta as in MDCCLVI, Line engraving by Thomas Kitchin, from Robert Orme's History, vol.II, London, 1778; 20 x 71.5 cm. |

|

|

9. Early view of Calcutta (unspecified origins) |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

|

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top | |

| 3. Calcutta: Society and Change: 1690 - 1990; "Growth of the Metropolis", by Samaren Roy Rupa & Co publishers,1991. |

| CALCUTTA is built on land that slopes east from the flood bank of the Hooghly to

a depression which is inundated by tides, and hence filled by salt water.

This depression was larger than it is now when it covers 28 square miles,

and possibly reached upto Entally in East Calcutta.

Job Charnock, having been once driven out of Hugli, wanted to assure himself that the new site for the English factory would be less vulnerable than the former to land forces. He was not apprehensive of an assault by water, for the Moghuls lacked even a flotilla, and the French and Dutch were not expected late in the 17th century to be contenders of power on the Hooghly. The Portugese who were strong and dominating, had been ousted by a land army. No cavalry can ride down a river or splash through a marsh, nor can an infantry wade through water. To drag field guns through a stretch of water would be still more difficult. So Charnock sited himself and his warehouse at a place to which access by land was restricted to a narrow strip of land between the Hooghly and the Salt Lake. The strip was three miles wide. Old temples point to the Hooghly having swept eastward in a meander which touched Garia to return to a point above the place where it receives the Damodar (see map). The ancient meander is now represented by Tolly's Nullah, which was turned into a spill channel for tides by the excavation in 1748 of obstructions, which enabled the use of the present navigable route. If the Dutch did any river training, that must have been before 1686, because Charnock used the channel to sail to Madras to enlist help, and returned to Sutanati. Alexander Hamilton , who was an "interloper" or "merchant" trading on his own without being part of the Company, came up the present route in 1705, and mentions that the English settled at Kalikata after "the Moghuls had pardoned all the robberies and murders committed on his subjects". Alexander Hamilton defiantly owned a house in Calcutta, which he asked the Council to register against a mortgage of Rs. 2,902. He thought that "a pretty good garden belonging to the Armenians across the river (that is, Howrah) would have been a better place to settle down". Hamilton provides information about the layout of Calcutta. Govindapur had a "little pyramid built as a landmark to confine the Company's colony". The Governor's House in the fort "is the best and most regular piece of architecture that I saw in India. And there are many convenient lodgings for factors and writers within the fort, and some storehouses for the Company's goods, and magazines for their ammunition". The fort was then roughly where the General Post Office is located now, to the west of Laldighi (which had a succession of names: Tank Square, Dalhousie Square, and now B.B.D. Bagh). The Company had a garden and ponds that furnished the Governor's table with vegetables and fish. About 50 yards from the fort was the Church of St. Anne, built in 1709. The construction of a hospital was begun in 1707. Residents were carried about on land in palanquins, and in bazras (budgerows) in water. According to Hamilton, Kalikata was preferred to Sutanati or Govindapur "for the sake of a large shady tree". Charnock used to draw on his hookah underneath it. The location and identity of that tree has been the subject of considerable speculation. Most investigators hold that Charnock's favorite was a pipal at the end of the avenue that led from his residence eastwards, later called Bow Bazar Street. At the eastern end is Baitakkhana, where Charnock used to make purchases of goods brought by land. The ancient pipal tree there was cut down i 1820 by a notification of the Governor-General. Others are of the opinion that a tamarind tree was Charnock's favorite and that his tomb was built near it. Neither the Governor's House nor the warehouse was fortified till 1696, when Shobha Singh's rebellion started. All armies on the move resorted to plunder and the wealthy moved away from their paths. The Dutch at Chinsurah could not remove their factory and so surrounded it by a high brick wall and mounted guns at suitable places. The English did the same at Kalikata, and named the construction after the reigning sovereign, Fort William. Hamilton the fort as a "irregular tetragon" built of brick and mortar, jostled by other houses, erected without order and in satisfaction of the convenience of their builders, accessible through gardens. The English had possession of the riverside of Kalikata, while Indians had property inland. In Sutanati and Govindapur, Indians occupied both the waterfront and inland sites. The Roman Catholics at Bandel who had been intolerant of Protestants till the end of the 18th century erected a brick chapel in Kalikata in 1700, to replace an earlier temporary structure. The present Cathedral, earlier called the Portugese Church, was built in 1799. The Armenians, too, built a place of worship with timber, later replaced by a masonry structure. Hamilton noted that "... in Calcutta, all religions are freely tolerated ... there are no polemics, except between the Governor's party and other private merchants on points of trade." At the beginning of the 18th century Calcutta was on its way to outstripping all its rivals. Hamilton mentions Chandernagore as having a "pretty little Church to hear Mass, which is the chief business of the French in Bengal". Chinsurah was a mile long, with many Armenian and Indian residents (the latter often seeking political asylum from inimical bureaucrats), while contiguous Hugli stretched for two miles along the river. Bandel had no trade but a large population of converts to Catholicism. The digging of the Marhatta Ditch in 1742 was significant for defining the city's boundaries, which remained unaltered for more than a century till the residential areas of Bhowanipore, Kalighat and Ballygunge were developed. The Ditch was covered in 1804 and converted into the Circular Road, but Ballygunge's status as part of Calcutta was uncertain till 1870. Bhowanipore was developed still later, in spite of the temple providing a nucleus and its being part of the property of the descendants of Tipu Sultan. One reason for the slow growth of areas beyond the Ditch was that till the 1753 conferment of the zamindary of the 24 Parganas, enterprising builders were attracted more to the Garden Reach waterfront than to inland parts. Three years after the receipt of the zamindary of the 24 Parganas, which till then had belonged to the Sabarna Roy Choudhurys, the Company found that the defenses of Calcutta, natural as well as artificial, were inadequate to prevent its being stormed. The natural defenses were the Salt Lake and the Hooghly. James Mitchell, who visited the the place in 1748, noticed "that the Governor's House and the Company's store and warehouses" were "surrounded by a high wall without a moat, with bastions planted with a few canon and a battery of 30 guns facing the river, and a feeble garrison". Mitchell thought the Fort could "resist a country but not a European force", although he noticed that the "houses of the British scattered at a small distance from the Fort, and formed a very irregular area in the centre", could impede the defense of the Fort. "The town of Calcutta is about two miles north of the Fort", wrote Mitchell, "open, without any defense of great extent", and inhabited by Hindus, Muslims, Portugese, Jews and Armenians. Old Fort William fell to a country force, and when a new fort was built it was ensured that it should not be hemmed in by houses. So the site of the new fort was shifted to Govindapur, and the residents - all Indians and no British - were evicted from their homes in October 1757. Those evicted included the ancestors of such illustrious men as Rabindranath Tagore, the Ghoshals of Bhukailash and the Devs of Sovabazar. The storming of the old Fort William in 1756 led to Calcutta acquiring its most characteristic features - a large open pleasance called the Maidan at the center and a rearranged central business district called Laldighi. Originally, Calcutta had only two roads; one by which pilgrims went to the temple at Kalighat. This north to south thoroughfare is still the main street of the metropolis, sections of which carry different names. The central section is Chowringhee (now renamed Jawaharlal Nehru Road), the northern section is Chitpur Road (now renamed Rabindra Sarani) and the southern section the Russa Road (nor renamed Ashutosh Mukherjee Road and Shyamaprasad Mukherjee Road). The other, called the Avenue, is at present Bow Bazar Street, running west to east. In the 1756 fighting between the English and Siraj-ud-dowla, not only the Fort but the Governor's House and St. Anne as well were destroyed. When the fort was rebuilt, so was the new residence for the Governor, called Buckingham House. It was on the site of the present Raj Bhavan or Governor's House. The Fort took a long time to build and was completed only in 1774. Near Job Charnock's tomb and where the tamarind tree stood, a new church was built in 1774 and consecrated to St. John's. Around 1740, the horse-drawn coach came to Calcutta. Its use was limited to the Governor and members of his Council. In the atmosphere of great optimism that prevailed after the recovery of Calcutta and the victory of Plassey (June 23, 1757), more Britons could afford coaches. We lack precise information on Robert Clive (Governor from 1757 to 1760 and from 1765 to 1767), who built two houses for himself; one north of Raj Bhawan, believed to have been his town residence. Daniell's drawing of Buckingham House is dated 1788, and it is possible that it was a late construction and Hastings did not use it as his residence. Hastings built a home for himself in Alipore, which is still there and in a much better state of preservation than Clive's at Dum Dum. The other important 18th century building is the Old Mint, and that in which the Bankshall Court is located. The latter is supposed to have been for a time the residence of Reza Khan, who had bought it from an Englishman. Belvedere in Alipore belongs to this period, and in 1780 Mrs. Eliza Fay called on a Mrs. Hastings who resided there. Two street names are also 18th century institutions. The Old Council House Street and the Old Court House Street are to west and east of BBD Bagh; Mitchell mentions that they were laid out wide and straight after the shelling of the Old Fort had destroyed the haphazard and irregular constructions around it. The Governor's Council met at the Old Council House, while the Mayor held his court at the Old Court House, which also served the purpose of a town hall, as balls, dances and other ceremonial gatherings were held on its upper storey. The site is now occupied by St. Andrews Church, built in 19th century and located on the east of the present Writer's Building. Old Fort William had provided residential accommodations to the Company's writers. On its destruction and removal of the Fort to Govindapur, the Company in 1780 leased a house built by Richard Barwell, a member of the Council. The house contained 19 apartments, each furnished with a set of outhouses. The building presently houses the West Bengal Government Secretariat. Rebuilt Calcutta was a compact little town arranged on the four sides of the Laldighi Tank and the garden around it; the Buckingham House, the Governor's residence and the St. John's Church to the south, the Deputy Governor's residence to the west, accommodation for the Company's writers and the Mayor's Court to the north. Behind the building for the writers at its northwestern end was the theater, which now houses commercial firms. Between the Fort and the Governor's residence was the Esplanade. Thomas Twining, who arrived in 1792, sailing up the Hooghly, describes the Esplanade as separating the Fort from the city. "A range of magnificent buildings, including the Governor's Palace, the Council House, the Supreme Court House, the Accountant General's Office, etc., extended eastward from the river, and then turning at a right angle to the south, formed the limit of both the city and the plain. Nearly all these buildings were occupied by civil and military officers of the Government, either as their public offices or private residences. They were all white, their roofs invariably flat, surrounded by colonnades, and their fronts relieved by lofty columns, supporting lofty verandahs. They were all separated from each other, each having its own small enclosure, in which the kitchen, the cellars, storerooms, etc. were at a little distance from the house, and a large folding gate and porter's lodge at the entrance." While coming up the Hooghly, Twining had passed Garden Reach, the city's residential quarters. It was a long reach running east to west. "Handsome villas lined the left or southern bank, and on the opposite shore there was the residence of the Superintendent of the Company's botanical gardens. It was a large upper-roomed house not many yards from the river, along the edge of which the garden itself extended. The situation of the elegant garden houses, as the villas on the left bank were called, surrounded by verdant grounds laid out in the English style, with the Ganges flowing before them, struck me as singularly beautiful." Twining missed noticing the banyan tree at the Botanics up a narrow creek. The tree is presumed to have been bird-sown on a date palm around the time the Battle of Plassey was fought, and had attained impressive proportions by the end of the 18th century. L. de Grandpre, a French visitor in 1789, found the Buckingham House on the Esplanade "handsome but by no means equal to what it ought to be for a Governor-General", to which rank the Bengal Governorship had been raised in 1774. But William McIntosh in 1779 felt that the Esplanade was "the only part of the city worth preserving." St. Anne's and the Armenian Church were both built in 1707; the Roman Catholic (Portugese) Chapel was raised to a church in 1799, and the Greek Church was built in 1780. Dates for the oldest temple and mosque are lacking. Shalom Aarom Cohen as the first Jew to settle in Calcutta in 1797. Tiretta Bazar was the first public market and it started functioning in 1783. (end of chapter) |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top |

| 4. Picture Gallery: Calcutta in the 19th Century

Source: 'Calcutta: City of Palaces' by J P Losty (British Libraries, Arnold Publishers); compiled by S. Mukherjee | |

| Click picture to enlarge | Description of Picture |

|

1. James Baille Fraser, View of Court House Street from the South Eastern Gate of Government House, 1819. Colored aquatint, engraved by T Fielding, plate 14 from 'Fraser's Views of Calcutta and its Environs', London, 1824-6'; 28 x 42.5 cm |

|

|

2. James Baille Fraser, A View of Writers Building, 1819. Colored aquatint, engraved by R Havell Junr, plate 6 from 'Fraser's Views of Calcutta and its Environs', London, 1824-6'; 28 x 42.5 cm. |

|

|

3. James Baille Fraser, A View of the West Side of Tank Square, 1819. Colored aquatint, engraved by R Havell, plate 22 from 'Fraser's Views of Calcutta and its Environs', London, 1824-6'; 28 x 42.5 cm. |

|

|

4. James Baille Fraser, View of St Andrew's Church from Mission Row, 1819. Colored aquatint, engraved F C Lewis, plate 13 from 'Fraser's Views of Calcutta and its Environs', London, 1824-6'; 28 x 42.5 cm |

|

|

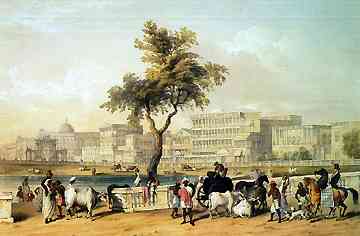

5. Shaykh Muhammad Amir, Government House and Esplanade Row from the Course, 1828-30, Watercolour; 33 x 74.5 cm; India Office Library Add Or. 4151. |

|

6. Sir Charles D'Oyly, Esplanade from Chowringhee Road, c. 1835. Coloured lithograph, plate 24 from his 'Views of Calcutta and its Environs', lithographed by Dickinson & Co., London, 1848; 21 x 44 cm. |

|

|

7. William Prinsep, Entertainment during the Durga Puja, c. 1840, Watercolour, 23 x 43.5 cm, India Office Library WD4035. |

|

|

8. Sir Charles D'Oyly, Chowringhee Road from No.XI Esplanade, c. 1835. Coloured lithograph, plate 26 from his 'Views of Calcutta and its Environs', lithographed by Dickinson & Co., London, 1848; 26 x 53.5 cm. |

|

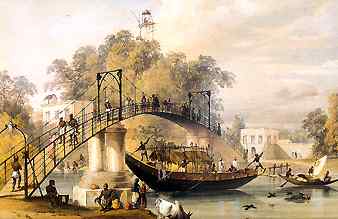

9. Sir Charles D'Oyly, Suspension Bridge at Alipore over Tolly's Nullah, c. 1835. Coloured lithograph, plate 20 from his 'Views of Calcutta and its Environs', lithographed by Dickinson & Co., London, 1848; 30 x 41.5 cm. |

|

|

10. Frederick Fiebig, panoramic view of Calcutta from the Octerlony Monument, in six parts. Lithograph published by T Black, Asiatic Lithograph Press, Calcutta, 1847; each 21 x 32.5 cm. |

|

|

11. Frederick Fiebig, panoramic view of Calcutta from the Octerlony Monument, in six parts. Lithograph published by T Black, Asiatic Lithograph Press, Calcutta, 1847; each 21 x 32.5 cm. |

|

|

12. Frederick Fiebig, panoramic view of Calcutta from the Octerlony Monument, in six parts. Lithograph published by T Black, Asiatic Lithograph Press, Calcutta, 1847; each 21 x 32.5 cm. |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

|

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top | |

| 5. Excerpts from 'Calcutta: City of Palaces' by J P Losty, The British Library, Arnold Publishers. |

| Although

references to the 'palaces' of Calcutta are found from as early as 1780,

the epithet 'The City of Palaces' was first used by James Atkinson as the

title of his poem published in Calcutta in 1824, which sums up feelings

expressed by many at this time. This will give the flavour:

A prodigy of power, transcending all The conquests, and the governments, of old, An empire of the Sun, a gorgeous realm of gold. For us in half a century,

India blooms

I stood a wandering

stranger at the Ghaut,

Page 11: 'August 24, 1690. This day at Sankraul ordered Capt. Brooke to come up with his Vessel to Chutanutte where we arrived at about noon, but found ye place in a deplorable condition, nothing being left for our present accommodation & ye Rains falling day & night. We are forced to take ourselves to boats which considering the season of the year is very unhealthy.' With these depressing words from the first volume of the Fort William Factory Records, Job Charnock, the Honorable East India Company's Chief Agent in Bengal, recorded the third and final occupation of a foothold of ground in Suttanauttee within the confines of the modern Calcutta, and so begins the history of that city. It was trade that sent the English and other Europeans to India, and it was obvious that the delta of the Ganges was the best place to establish a trading station. Bengal was the richest province in India, while downriverfrom the Ganges, Jumna and their tributaries came the goods of all Hindustan. When the Portugese arrived in Bengal about 1518, two great ports were alreadu established there, Chittagong in the east (which did not control the Ganges trade) and Satgaon in the west, an ancient town originally on a branch of the river Hooghly (itself the western-most branch of the Ganges delta) about 30 miles upriver from Calcutta. Satgaon's importance was diminished by the gradual silting up of its river, and about 1550 some of its Indian merchants, families of Bysacks and Seths, transferred themselves downriver to the site of modern Calcutta, to the villages of Gobindpore on a slight eminence above the river, and Suttanutte, where an important market for cotton, the principal trade of Bengal itself, was developing. The bend of the river just below was its last easily navigable stretch, and a temporary town at Betor on the west bank had sprung up to service the traders during the season. Further upstream the river shallowed, and the Portugese used to send river boats to bring down the goods from Satgaon. About 1575, however, the Portugese received permission from the Emperor Akbar to found a settlement at the town of Hooghly, and they prepared to bring their ships further up while enjoying the Emperor's goodwill. Betor was largely abandoned and its trade transferred to Suttanutte across the river. Akbar demanded in return that the Portugese at Hooghly should keep the eastern seas free of the renegade Portugese and Arakanese pirates from Chittagong and the Arkan who infested them. However, the tolerance of Akbar's successors for the presence of the European infidels was easily upset, and the Portugese failure to fulfill their part of the bargain drew the vengeance of Shah Jahan upon them. In 1632 Hooghly was captured by the Moghuls after a three month's siege, and its Christian survivors were transferred to Agra as slaves, ending all serious Portugese economic activity in Bengal. Page 13: The Company divided its servants into ranks: 'Knowing that a distinction of titles is, in many respects, necessary, we order that when the apprentices have served their times they be styled writers; and when the writers have served their times they be styled factors; and the factors having served their times be styled merchants; and the merchants having served their times be styled senior merchants.' In the factories they lived a kind of collegiate life, with meals taken in a common hall, seated in strict order of seniority, but apparently with groaning tables before them, with arrack punch and Shiraz wine to drink ... Page 16: Between Suttanutte and Gobindpore was another village, Calcutta, in 1690 the least important of the three, but destined to give its name to the whole city. The name Calcutta (Kalikata) has nothing to do with the temple at Kalighat, as is still often supposed, as the two were distinct places even in the 15th century, when both places are mentioned by the Bengali poet Bipradas ... |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top |

| 6. Adapted from "The Calcuttan" (page 31 - 38) by Samaren Roy; "Calcutta: Society and Change - 1690 - 1990"; Rupa & Co. publishers; 1991. |

| Bengal was intermittently

a part of the Delhi Sultanate till 1580, when Akbar absorbed the province

into the Moghul Empire. Man Singh was the first Moghul Viceroy, and he

governed from Rajmahal on the Ganga, above the point whence the most easterly

distributary - called the Bhagirathi in the upper reaches and the Hooghly

in the lower - branches off. On his second trip in 1612, Man Singh entrusted

the collection of rent in lower Bengal to the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family,

who are still illustrious, having produced generations of members who attained

eminence.

The Roy Choudhury's could collect rent only from those areas which had come under cultivation, or where spinning and weaving produced items which could be subjected to levies. Most of the delta or the southern part of the demesne was too marshy for cultivation. Mangrove swamps extended to the neighborhood of Sealdah, one of Calcutta's present rail termini; the locality known as Entally derives its name from hatal pneumatophores which grew there. The Roy Choudhury's were at Halisahar - 46 km north of Calcutta - till the middle of the 16 century. Later, they shifted to Gopalpore in the Hooghly district, then to Birati and finally to Barisha, 10 km south of the city, where it has remained till now. The spread of cultivation southward was slow and till the end of the 18th century, Kulpi - 66 km south of Calcutta - was the last village on the south bank. It was from Barisha that the Roy Choudhury's leased out three east bank villages of Sutanati, Kalikata and Govindapur to the English East India Company in 1698, five years after Charnock's death. Tidal creeks , later filled up and obliterated, separated the villages from each other. The memory of one of these tidal channels lives on in the name of 'Creek Row' - a lane extending eastward from Subodh Mullick (formerly Wellington) Square. Sutanati was probably the more ancient of these three habitations. It was definitely the most populous and prosperous, engaged in the production and export of cotton textiles; till 1632 selling its produce to the Portugese ships anchored at Betor on the opposite bank. Fisherfolk lived at Govindapur, the most southerly of the three villages. It was small and thinly populated, where an indigent and nearly ostracized Brahmin family lived as a priest for the fisherfolk. The family's surname in the 1700s was Kushary, which changed to Thakur (rendered into English as Tagore), because their fishing clientele addressed them as such. Thakur means lord and is the honorific of priestly groups in Bengal, and of land-owning castes in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The adoption of the new surname erased the stigma associated with a polluting event. There were also other Brahmins and Kayasthas settled there, notably the Halders of Kalighat. Information about the population of Kalikata and their vocations around 1690 is scant. The Roy Choudhury's, who were also Brahmins, had a kutchery there to collect rents, presumably from all the three villages. To the east of the kutchery was a tank, which turned red during the colour-sprinkling festival of Holi each spring, and thus earned the name of Laldighi, or red tank. However, much had happened before the English leased the three villages from the Roy Choudhurys, The English East India Company had been a latecomer in trade with India, and entered it following the visit of Sir Thomas Roe to the court of Jahangir. Trading centers were established at Surat, Madras and Vizagapatnam before the Company came to Balasore, further east. The expulsion of the Portugese from the Hugli and all Moghul territories created an opportunity for the English to move in. An English factory was established at Golghat in Hugli town in 1650, with subordinate establishments at Cossimbazar for silk and indigo, at Patna for indigo and at Hajipur for saltpetre. Job Charnock had served at Hajipur and Patna before moving into Hugli. In upcountry Bihar, he had saved a widow from being burnt on her husband's funeral pyre. Charnock made her his wife, and lived with her till her death at Sutanati. Meanwhile at Hugli, Charnock and the factors fell foul of Shaista Khan, the then Moghul Governor, and after a brief fight in 1686-87, the company was expelled from Bengal. While Charnock was reporting to the Company's Indian headquarters, then at Madras, there was a change in the governorship of Bengal. Ibrahim Khan, who replaced Shaista Khan, was more receptive to the company's pleadings. The name of the Company's pleader is buried in a mass of correspondence, but it is likely that it was Khoja Sarhad Khan, as he acted as a pleader as well as interpreter in 1698 and 1715. Khoja Sarhad was a shipowner and merchant, who became a prime factor for the Armenians in Calcutta after receiving a charter to trade in 1688. Unlike the Europeans, the Armenians had little political identity. Their home country was ruled by the Ottoman Sultans of Turkey and the Safavid Shahs of Persia. But they were Christians and had little in common with their rulers, both of whom were Muslims. They befriended Humayun when he was a refugee at the Persian Court during the middle decades of the 16th century and followed him back to India. Being at home in Persian, which was also the language of the Moghul Court, they often found employment in civil posts and occasionally in the army. But they were mainly traders. There was a large Armenian community at Chinsurah, and the influx continued. Khoja Sarhad was a late arrival, and it is debatable where and when he learned English sufficiently to serve as interpreter to John Surman's mission to Delhi in 1715. His standing with the Moghul princes was good enough to enable the English Company to secure the permanent leases of the three villages in 1698, obtained from Azimushan while he was still the Viceroy in Bengal. Azimushan later became Emperor Jahandar Shah in 1712, but was murdered the following year. Farrukhsiyar, son of Azimushan (Jahandar Shah), marched from Bengal to claim the throne and rule till 1719, The Surman mission was to Farrukhsiyar's court and commanded the good offices of Khoja Sarhad, as both interpreter as well as negotiator. His task was made easier by William Hamilton, surgeon accompanying the mission, curing Farrukhsiyar of a disease which till then had resisted treatment. Under the new firman issued by Farrukhsiyar, the English were conferred not only the right to reside and trade in Moghul territory, but their goods were also freed from duties, imperial or local, except for an annual payment of Rs 3000. The misuse of this right was later to lead to friction with the Nawab Nazims, the rank to which the subedars were elevated. The concession put the English Company at a decisive advantage vis-a-vis their French and Dutch rivals. Another advantage was that from 1698 - thanks to Khoja Sarhad - the English owned a continuous tract of land 12 km long and 4 km wide through a permanent lease, whereas the three settlements of their rivals stretched along 25 km, separated from each other stretched along 25 km, separated from each other and surrounded by Indian landowners. The English, however, did little to convert this compact estate into a defensible position. Even after Shobha Singh's rebellion in 1696, only the warehouse was provided with fortifications and guns of a sort whose efficacy was severely hampered by allowing haphazard private constructions around what was called Fort William. The only defensive work undertaken was the digging of the Marhatta Ditch in the 1740's when the Bargis had appeared in the Burdwan and Birbhum areas. The Bargis were bought off by Nawab Nazim Alivardi Khan. The ditch was not even a continuous moat. In any case, neither the ditch nor the Fort William proved any obstacle to Siraj-ud-dowla in 1756. The ditch served only one purpose: to earn the English residents of the city the nickname 'Ditchers'. The Armenians and others were excluded from this description, and to this day they are known as Calcuttans. What about the English between 1690 and 1740? The best nomenclature for them would be Charnockites, by which English geologitsts designated a rock which till then had not been found anywhere. Armenians became an important constituent of Calcutta. Khoja Sarhad was not the first of his people to come to Calcutta. A tombstone for Sookea's wife, who had died in 1630, was found in 1884. The Sookea's probably resided at Sutanati or Howrah, where the Armenians had a garden throughout the 18th century, and which might have existed in the previous century. Next to the Armenians, the Suvarna Baniks were an important local trading community. They worked as cashiers for Clive and Hastings, became powerful in their own ways and founded houses like Cossipore and Jorasanko Rajas that remained important till recent times. Other legendary figures include Gouri Sen, the families of the Dhars of Posta (Burrabazar), the Mitras, the Mullicks and the Dutts. There is evidence that Brahmins resisted the attractions of settling down in Charnock's city. The Roy Choudhury's, who settled at Barisha after leasing the three villages over to the Company, did not usually travel the ten kilometers to experience the amenities that were becoming available at Calcutta. Their neighbours, the Behala Roys, were descendants of migrants. Their ancestor, a Chatterjee, had looked after the treasury at Satgaon during Jehangir's reign, and became 'Roys' as a result. When Shahjahan marched to sack the Portugese at Hugli, the family crossed the river to Halisahar, home of the Roy Choudhury's before they settled at Gopalpur, Birati and then Barisha. They moved again, this time to Madhyamgram, 21 kn nearer to Calcutta. After the scare caused by the appearance of the Bargis, they sought the comparative security of their present residence, four miles south of the Marhatta Ditch, but not within it. Behala, however, did not prove to be as secure as the Roys had hoped. Soon after, they began to build a house (the construction lasted from 1743 to 1860!). Raghu dacoit raided and hacked an arm off one of them. The temple built by the 18th century dacoit is still there, then two kilometers outside the city limits, but now within, on Purna Das Road in Ballygunge, Raghu had threatened to to pay a visit again, but did not. Krishnachandra Ray used to travel the 116 km from Krishnanagar to meet Sir William Jones, towards the close of the 18th century. However, he chose not to have a house in the city. The family later built a house in east Calcutta Learned Brahmins and reputed priests came much later to the city, after 1774, as advisers on Hindu law before the courts. For example, the Tarkabagish, who remained ambiguous on burning of widows; and as residents in the 19th century - Rammohun Roy, Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar and Ramkrishna Paramahamsa. The Tagores - who were Pirali Brahmins - found a refuge at Govindapur from 1700, and at Pathuriaghata and Jorasanko after 1760; they faced a kind of ostracism, for it was alleged that the aroma of cooked beef had entered their nostrils! All temples, at Dakhineswar, Kalighat and Tollygunge - except for a temple built by Gouri Sen in Burrabazar, the Navaratna temple built by Gobindaram Mitra and the older Chitteswari temple - were beyond the area enclosed by the Ditch. Brahmin reluctance to live in Calcutt may have prompted Warren Hastings to locate the Sanskrit College at Varanasi, and the Madrassah at Calcutta. Till the late 19th century, Banik pupils outnumbered Brahmins and Kayasthas in the city schools. This fact influenced the Bengal Renaissance movement in its early stages, for the debates were mainly between the Banias, although the reformist leadership remained with the Brahmins: Rammohun Roy, Dwarkanath and Prasanna Tagore, Tarachand Chakravarty, Dakshinranjan Mukherjee and Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar. Immigration from the villages during the 19th century so altered the population pattern that by the 1911 census - the last to enumerate people by castes - Brahmins and Kayasthas were the two largest, numerically matching each other. The other groups became numerically weaker, and no longer wielded their earlier influence. During the 192 years of Portugese presence at Hugli, a community referred to as Portugese first, then 'Topasses', Feringhees and Eurasian at last, came into existence through conversions and intermarriages. Similarly, at Chinsurah, the Dutch brought Malay women, who were reputed to be beautiful. The Portugese after 1632, and the Dutch after 1824, became dispersed. They were attracted to Calcutta as it was the only flourishing and nearest urban center. Henry Derozio could have been of Portugese descent, but he preferred an India identity, and became a leading figure in Bengal Renaissance in early 19th century. His senior contemporary, Alexander Skinner, who had an English father, became a soldier of fortune and the cavalry unit he raised became a part of the Indian Army; it had armored vehicles for conveyance and bore a different name. The Muslim community in Calcutta had mostly drifted in from Mysore (Tipu Sultan's descendants), Murshidabad and the Oudh entourages, and generally did not form part of the city's life. Of the few who did, were Mirza Abu Taleb, who was the first person from the city to travel to Europe at the end of the 18th century, and returned with the idea of progress; this influenced the Bengal Renaissance to a great extent. The Oudh entourages, of course, introduced North Indian music and dance to Calcutta. (end of chapter) |

| DISCUSSIONS:

Comment # 1: Received from |

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top |

| 7. Old Maps of Calcutta

Source: 'Calcutta: City of Palaces' by J P Losty (British Libraries, Arnold Publishers); compiled by S. Mukherjee |

| Part 1:

The maps in PART 1 record the progressive growth of Calcutta in the following phases: |

| Phase

1:1690 - 1757 > Phase 2:1757 - 1798 > Phase 3:1798 - 1858

The fourth map is a 'Plan of Calcutta, 1825' - engraved by M M Woollaston, and scanned from 'Calcutta: City of Palaces', by J P Losty; (back cover). |

| Note: The four pictures (which have been placed on one page to facilitate comparisons) total approximately 90 kB, and may take a while to load. Please be patient.

|

| PART 2: This section is an ongoing compilation of maps relevant to the historical explorations of Calcutta:

#2. Conjectural map of Calcutta at the time of the British advent, taken from 'Calcutta: Society and Change; 1690 -1990, by Samaren Roy, 'Introduction'. |

| Home | Roots | Creative Forum | Future Vision | Stop'n Look! | Contact Us | Return to Top |

|

Quiz - time!!! ready...get set...GO!

If you do not know any of the answers, click on the link to 'view' the 'answer'... ... but first, you must enter your name please: |

|

Q1. Job Charnock chose the site for Calcutta on the east bank of the Hooghly on August 24, 1690 (true or false)?

(in words; lowercase)

Q2. The Hooghly has been an important waterway for more than 3000 years (true or false)?

Q3. The epithet 'The City of Palaces' was first used as the title of a poem by ___________.

Q4. The three habitations that the Roy Choudhury's leased out to the English East India Company in 1698 were Govindapur, Kalikata and _____________ (hint: it is also the more ancient of these three habitations)

Q5. In early 19th century, Henry Derozio became a leading figure in ________ ________.

Your score this time: percent Please tell us if you have any inputs to improve this pop quiz. Thank you. |

| If you

find our presentations not up to your expectations, or if you do not see

the article/contribution(s) which may have been archived due to paucity

of disc space, please contact us/use the feedback form, or mailto:sankalpatrust@hotmail.com

We shall succeed only with your active participation in these processes. Please send in your comments about our presentations, and your own contributions for inclusion in this page. Meanwhile ... |

© 2000 Sankalpa Trust